Article: Silver, I. A., Cochran, J. C., Motz, R. T., & Nedelec, J. L. (2020). Academic Achievement and the Implications for Prison Program Effectiveness and Reentry. Criminal Justice and Behavior. https://doi.org/10.1177/0093854820919790

1. Background (PDF)

Incarcerated populations typically exhibit lower educational attainment and literacy than the general public, with persistent disparities in reading, writing, and numeracy. These educational deficits can compound barriers to successful reentry by limiting employment opportunities, social stability, and participation/success in rehabilitative programming. While research has long recognized education as a protective factor against criminal behavior, less is known about how academic achievement affects outcomes after incarceration—particularly whether verbal and math abilities influence recidivism and the effectiveness of recidivism-focused programs offered within prisons. The beneficial effects of recidivism-focused programs—such as cognitive-behavioral interventions, vocational training, and family skills courses— does vary across participants, raising questions about “what works for whom.”

The current study integrates these perspectives to evaluate whether academic achievement influences both recidivism and success during reentry after receiving recidivism-focused programs. Specifically, the authors examined whether verbal and math performance predict reincarceration risk and whether academic achievement modifies (i.e., amplifies or undermines) the effects of program completion on reentry success.

2. Summary of Findings

Direct Effects: Lower academic achievement was associated with a higher likelihood of recidivism in the first year after release but not at two- or three-year intervals. This suggests that academic skill deficits exert their strongest influence during early stages of reentry.

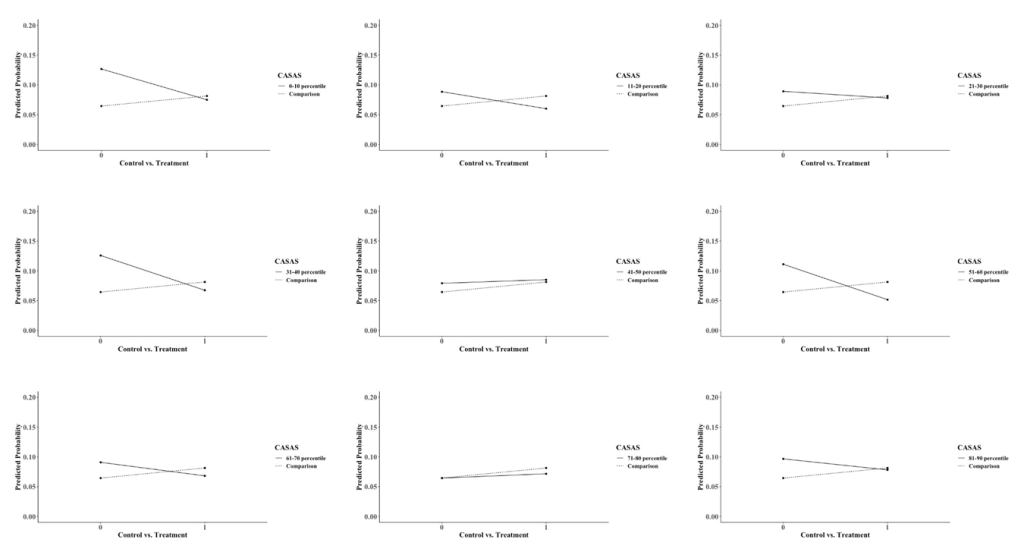

Moderation Effects: Academic achievement altered program effectiveness for some individuals. Specifically, reentry programs produced greater reductions in recidivism among individuals with lower academic achievement. For example, those in the 31st–40th and 51st–60th CASAS percentiles experienced the largest decreases in reincarceration risk following program completion compared with peers in the highest achievement decile (91st–100th percentile). For example, for those individuals in the 31st–40th CASAS percentiles, program completion reduced the probability of recidivism from roughly 14% to 6% (See Figure 1).

Together, these results suggest that educationally disadvantaged individuals could benefit from evidence-based prison programming, a finding that challenges assumptions that lower academic skills hinder rehabilitation.

3. Implications

Target Low-Educational Achievement Individuals for Programming Access: The findings suggest that individuals with lower academic achievement derive the greatest benefit from participation in recidivism-focused programs. Correctional agencies should also prioritize program enrollment for low-literacy or low-achievement individuals, as well as aligning case plans with the criminogenic needs of an individual to ensure rehabilitative resources have the greatest benefits for incarcerated individuals.

Integrate Education and Behavioral Interventions: The synergy between cognitive-behavioral treatment and educational skill-building suggests that integrated programming may yield the strongest outcomes. Programs should embed literacy and numeracy instruction into reentry curricula and align educational goals with behavioral change content.

Enhance Program Completion Among Educationally Disadvantaged Individuals: Since program completion—not merely participation—was linked to lower recidivism, administrators should focus on strategies that increase completion rates among high-risk, low-educational achievement participants. Interventions could include remedial tutoring, simplified instructional materials, and smaller group sizes to accommodate varying comprehension levels.

Monitor and Evaluate Responsivity Factors: Academic achievement operates as a “responsivity factor” in the Risk–Need–Responsivity (RNR) model, influencing how individuals respond to interventions. Correctional systems should routinely collect and analyze academic and cognitive data to tailor programming and improve responsivity alignment.

4. Data and Methods

Using administrative data from the Ohio Department of Rehabilitation and Correction (ODRC), the study analyzed a statewide sample of 13,536 incarcerated individuals (4,603 who completed recidivism-focused programs and 8,933 with no program exposure). The analysis used the Comprehensive Adult Student Assessment Survey (CASAS), a standardized reading and math test administered at prison intake, as a measure of academic achievement. Scores were divided into 10 percentile categories to assess nonlinear effects.

Recidivism was defined as reincarceration for a new crime within one, two, or three years post-release (excluding technical violations). Program completion included evidence-based cognitive-behavioral or life skills interventions such as Thinking for a Change, Inside Out Dad, and Victim Awareness—all shown in prior ODRC evaluations to reduce recidivism.

A propensity score matching (PSM) approach was employed to balance treatment and control groups across twelve covariates (e.g., age, race, security level, prior sentences, misconduct, marital status). Logistic regression models then estimated the main and interactive effects of academic achievement and program completion on recidivism at one, two, or three years post release. Marginal probabilities were produced to ease the interpretation of the interaction effects.

5. Conclusion

The study provides compelling evidence that academic achievement is both a risk and a responsivity factor in reentry outcomes. Lower academic achievement increases short-term recidivism risk but also enhances responsiveness to effective programming. These findings support expanding educational assessment and targeted interventions within prisons, particularly for those at the greatest educational disadvantage. Integrating academic skill development with behavioral programming and ensuring equitable access to these interventions could reduce recidivism, improve reentry success, and enhance public safety.

Notes: The comparison cases represent the 91-100 percentile on the CASAS exam. The control cases represent individuals who received no programming. “*” represents a p < .05 difference between the predicted probability of the control and treatment cases for the specified CASAS percentile. “±”represents a p < .05 difference between the slope of the specified percentile and the comparison cases.

Disclosure: This research brief was prepared by ChatGPT and reviewed/edited by Ian A. Silver.