Article: Silver, Ian A., & Nedelec, Joseph L. (2018). “Ensnarement During Imprisonment: Re-Conceptualizing Theoretically Driven Policies to Address the Association Between Within-Prison Sanctioning and Recidivism.” Criminology & Public Policy, 17(4), 1005–1044. https://doi.org/10.1111/1745-9133.12397

Over the last three decades, life-course criminology has deepened our understanding of criminal behavior, with various theories contributing to the development of this field. One well tested life-course perspective is Terrie Moffitt’s developmental taxonomy. Of importance for the published article was Moffitt’s ensnarement hypothesis. The ensnarement hypothesis argues that repeated exposure to negative life events cuts of access to employment, family, income, and health care which, in turn, makes offending one of the few methods for maintaining basic life requirements (e.g., housing, food). Research has long examined the criminogenic consequences of sanctions imposed by the criminal legal system in the community. However, little work has focused on within-prison sanctions—formal punishments administered during incarceration.

Within-prison sanctioning includes practices such as disciplinary segregation (solitary confinement for disciplining behavior), elevated security classification, and removal of privileges. These practices are designed to maintain the safety and security of the correctional facility for confined individuals, guards, and civilians. However, the process of disciplining an individual within a correctional facility may unintentionally reinforce offending behavior. In particular, it could restrict opportunities to participate in and complete rehabilitation, educational, or vocational training. Moreover, they could limit contact with civilians who could provide employment and educational opportunities upon release. As such, while much of the literature has focused on how within-prison sanctions deprive individuals, the frequency of sanctioning could cut off rehabilitation efforts and, in turn, increase recidivism.

If this is the case, the frequency of sanctioning, rather than the severity of any single punishment, is central to understanding how within-prison sanctions influence future offending. Silver and Nedelec (2018) sought to re-examine the link between within-prison sanctioning and post-release recidivism using Moffitt’s ensnarement hypothesis. By employing a large administrative dataset and a longitudinal analysis, the study provided one of the most comprehensive assessments of within-prison sanctioning to date.

2. Summary of Findings

The analysis drew on data from the Evaluation of Ohio’s Prison Programs, which captured information on over 100,000 incarcerated individuals between 2008 and 2012. The analytic sample of 63,772 inmates represented one of the largest samples ever used to study within-prison sanctioning and recidivism. Sanctions were defined narrowly as rule infractions that resulted in a guilty finding by a rules infraction board, ensuring that only formal and substantive punishments were considered.

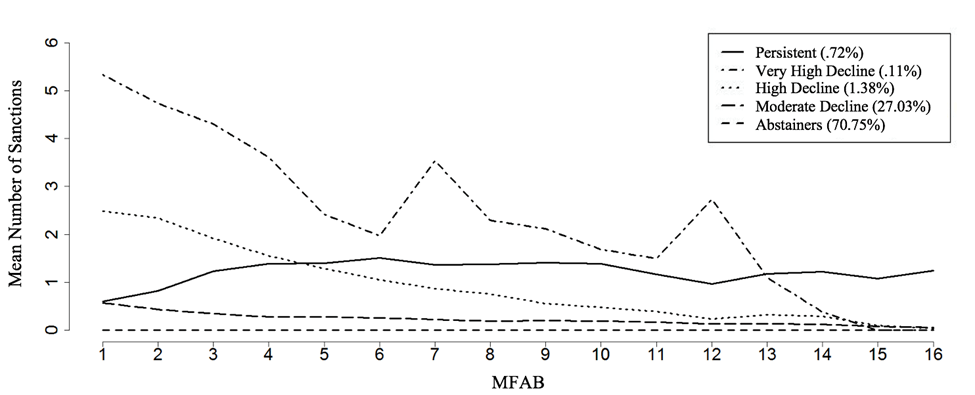

Using latent class growth analysis (LCGA), the study identified five distinct sanctioning clusters (Figure 1):

Abstainers (70.75%): Incarcerated individuals who received no formal sanctions during incarceration.

Moderate Decline (27.03%): Incarcerated individuals with moderate levels of sanctions early in their sentence that declined steadily across imprisonment.

High Decline (1.38%): Incarcerated individuals with high levels of sanctions early in their sentence that declined steadily across imprisonment.

Very High Decline (0.11%): Incarcerated individuals with very high levels of sanctions early in their sentence that declined steadily across imprisonment.

Persistent (0.72%): Incarcerated individuals that were consistently sanctioned at higher rates throughout incarceration.

Notes: N = 63,772; “MFAB” (months from admission blocks) represents three-month time frames (e.g., MFAB 2 is any sanction that occurred during the third month of incarceration and before the sixth month of incarceration); mean values for each MFAB are presented in Table B1 in Appendix B; the values in parentheses in the legend represent the percentage of the overall sample that falls into the specified sanctioning cluster.

The sanctioning clusters predicted reincarceration for a new crime 1-year post release, 2-years post release, and 3-years post release. In particular, individuals in the High Decline, Very High Decline, and Persistent groups were substantially more likely to be reincarcerated for new crimes at all three follow up periods. The results demonstrated that exposure to frequent sanctions during incarceration significantly heightened recidivism risk, supporting the notion of ensnarement during imprisonment.

3. Implications

The findings carry critical implications for correctional policy and practice.

First, the study underscores the need to expand access to rehabilitative opportunities during sanctioning periods. Instead of excluding sanctioned inmates from educational, vocational, or rehabilitative programming, correctional agencies should maintain or even increase opportunities for engagement. Such access could mitigate the exclusionary effects of sanctioning, helping individuals sustain networks and develop the skills necessary for successful reentry.

Second, the study highlights the importance of limiting the frequency of exclusionary discipline within-prison. While misconduct cannot be ignored, repeated reliance on punitive measures that exclude individuals from programming may undermine long-term rehabilitation goals. Reducing reliance on disciplinary segregation, security upgrades, and removal of privileges could provide individuals with continued opportunity to engage in rehabilitative programming increasing their ability to successfully reenter the community.

4. Data and Methods

The data originated from the Ohio Department of Rehabilitation and Correction (ODRC) and were collected as part of the University of Cincinnati’s Evaluation of Ohio’s Prison Programs. The study included 63,772 inmates incarcerated between 2008 and 2012, excluding juveniles and those with incomplete follow-up.

4.1. Measures:

Sanctioning: Defined as formal guilty findings and sanctions following rules infraction board hearings, covering infractions such as violence, drug possession, property damage, disturbance, escape, and weapons violations. Only guilty findings were counted to avoid officer-level bias.

Recidivism: Defined conservatively as reincarceration for a new crime within one, two, or three years after release. Technical violations were excluded.

Controls: Included demographics (age, gender, race, ethnicity), prior prison terms, cognitive ability, static risk scores, security classification, participation in programming, sex offender status, and mental health treatment.

4.2. Analytic Strategy:

The study applied LCGA to identify clusters of sanctioning patterns across 16 three-month intervals of incarceration. Abstainers (70% of inmates) were removed prior to modeling to focus on those with at least one sanction. Logistic regression analyses then assessed whether cluster membership predicted recidivism, controlling for covariates.

4.3. Key Strengths:

Extremely large, statewide sample.

Rigorous definitions of sanctioning and recidivism.

Integration of advanced longitudinal modeling (LCGA) with regression analyses.

5. Conclusion

Silver and Nedelec (2018) provide strong evidence that frequent exposure to within-prison sanctions increases the likelihood of recidivism after release. By demonstrating that sanctioning clusters predict reincarceration independently of background characteristics, the study advances both theoretical and policy discussions.

The research repositions sanctioning not merely as a necessary management tool but as a potential mechanism of ensnarement. Individuals subjected to frequent sanctions lose access to rehabilitative opportunities, reducing their chances of successful reentry. This insight shifts attention from the short-term management of misconduct to the long-term consequences of correctional practices for public safety.

In practical terms, correctional systems should prioritize ensuring sustained access to rehabilitative programs even for sanctioned inmates and reducing sanction frequency. Adopting policies aligned with the ensnarement hypothesis could help correctional institutions strike a balance between institutional control and reintegration, ultimately lowering recidivism and promoting public safety.

Disclosure: This research brief was prepared by ChatGPT and reviewed/edited by Ian A. Silver.